Exhibition of Olim Kamalov

The art of Olim Kamalov has a very specific peculiarity: it combines the features of a very old tradition and brings it to our times. He has absorbed the many century-old skills and ideas developed and perfected in Central Asian arts and crafts, including book and monumental art, mainly known in the form of murals. The earliest and the most famous of these originate from the Penjikent architectural complex, now mainly kept in the Hermitage Museum. For several generations the Penjikent frescos have been at the centre of the scholarly attention of international groups of experts, who agree that those murals carry the influence of many cultures which were in circulation in pre-Islamic and early-Islamic Transoxania: not only local Soghdian, Bactrian, or Khwarazmian but Hellenistic, Chinese and Buddhist.

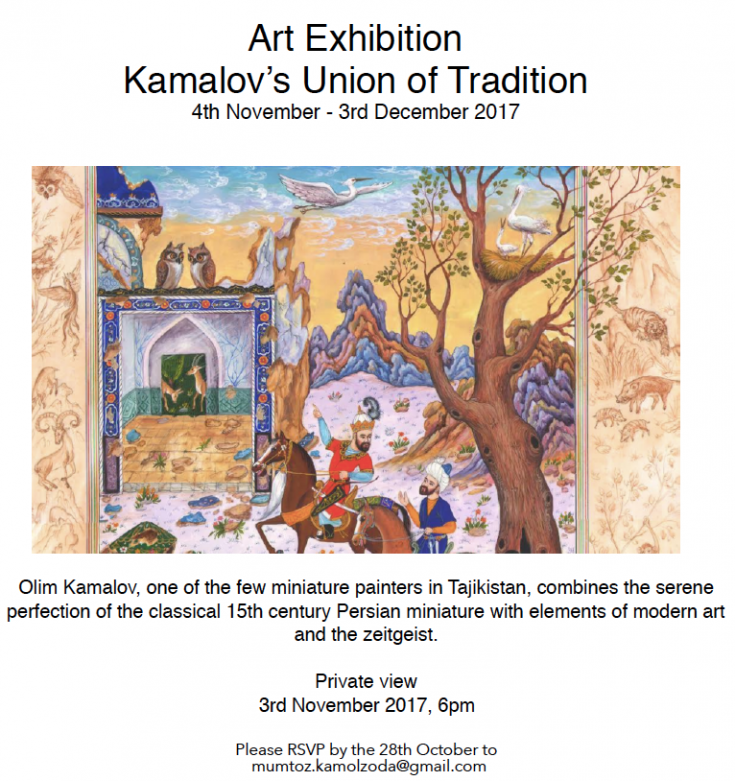

Being born in such an area of the historical melting pot of various cultural traditions, Kamalov absorbed them with the air, although the main source of his inspiration has been miniature painting at its peak, for which reason we see so many pieces directly related to the works by the main geniuses of the Golden age of Persian manuscript art, like Behzad (15-16th century), or Reza-yi Abbasi (17th century).

Apart from some exceptionally masterful emulations of these and other most prominent medieval Persian painters, it is important that Kamal’s art contains not only pure replications, which is also a part of the local tradition spread and kept until our days, both in visual art and especially in the literary culture of the Iranian-speaking, and more generally, Muslim world. In the introduction to his immortal collection of historical anecdotes, the Chahar Maqala (Four Discourses), Nizami Aruzi Samarqandi explained the criteria according to which a person in the 12th century would be considered an educated and sophisticated courtier, a man of letters and the arts. Before someone would be qualified for a job of a nadim (boon companion of a ruler) in the role, for example, of a poet or an advisor/secretary (dabir), whose functions could be stretched from those of a personal assistant to those of a minister (vazir), he would have to memorise thousands of lines of their predecessors’ verses. The purpose of such training would be to learn the existing techniques in their best specimens and try to surpass them, standing on the shoulders of the giants. Thus the phenomenon which sometimes in Europe could be qualified as slavish imitation and sometimes even plagiarism, in the East, and in the Muslim world in particular would normally be perceived as a sign and part of the best quality education.

The same idea would apply to the visual artists, as first they had to familiarise themselves with the masterpieces of the past, perfect themselves in imitating and emulating the best works before being able and entitled to create their own pieces, offering their own ideas, or their own interpretations of the existing artefacts.

One of the most important features of Kamalov’s works is that he skilfully combines the high quality folk crafts with arts developed at the royal ateliers, or mediaeval kitabkhanas.

He gets his inspiration partly from the famous and easily recognisable images from the unique manuscripts kept in the world’s museums and libraries, like Firdawsi’s Shahnama from the National Library of Russia, the manuscript which was brought to St Petersburg by Persian Prince Khosrow as part of the Redemption mission after the murder of Griboedov, or the Hermitage Khamsa by Nizami. Among the works of this kind are the Mi’raj of Muhammad, Majnun in the desert, or parts of the double page compositions of the frontispieces.

Apart from the well-known paintings, Kamalov is charmed by the pieces produced by unknown artists at the Mughal provincial ateliers with a very prominent Indian iconographic paradigm, or single standing figures of courtiers and youths characteristic of the late Safavid period, influenced by European painting.

However, he does not only merely reproduce them but applies different techniques and materials: transferring them from paper to wood, or ceramics, turning them from rectangular shapes to round, using various arabesque ornaments in the frames.

Of special interest are his original paintings depicting various episodes of everyday life in contemporary Tajikistan, both in towns and in rural areas. His rustic scenes are particularly curious as they have all the features of the traditional and rather generic decorative illustration programme of medieval miniature painting but present a number of very truthful details of real peasant life in Tajik villages, celebrating their feasts, like weddings, New year (navruz), a paradisiacal revival of blossoming nature in spring, or thematic scenes, like kite runners, an old man talking to a young girl by a mountainous stream, a loving couple under a blossoming tree wearing contemporary Tajik national dress. Kamalov’s successful attempt to connect through his works in such ways, Persian and Indian past with Tajik present, traditional crafts and high art, is his main contribution to modern Tajik visual culture.

Gallery